*What disappears in the discussion of motherhood and faith is the relationship of both to race.*

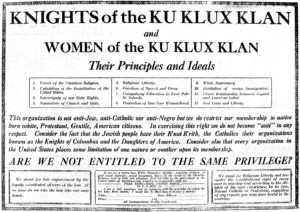

In 1924, Robbie Gill, the Imperial Commander of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK), gave a speech entitled “American Women” at the annual Klonvocation (Klan speak for convention) of the Ku Klux Klan (1915-1930). She proclaimed:

We women of America love you men of America….We will mother your children, share your sorrows, multiply your joys and assist you to prosper in the way of this world’s good. In return, we expect you to recognize our power for good over your lives, and in the nation….We pledge our power of motherhood to America….Our knees can be the altars of patriotism to them.

For Gill, just as mothers parented children, they could also parent the nation. Maternity functioned as a claim to authority in public spaces, and she let Klansmen know that women as mothers could change the nation for the better. Gill, however, was not satisfied to let men (even Klansmen) dictate national politics and policies.

Women with the “power of motherhood” could improve a nation in tumult and help reclaim white Protestant America for “true” Americans, white Protestants. Gill employed motherhood as a method to force Klansmen to pay attention to the WKKK and its efforts. Importantly, she showcased that women were as interested and invested in nation as men were, if not more so. A broken nation jeopardized a mother’s family, particularly children, so white mothers claimed that they must be the ones to fix it.

Christian Motherhood

Motherhood was only one component of Gill’s agenda to reform; she also asserted that faith was essential. Protestantism, for the Klanswoman, became the venue to correct national ills, reestablish a previous status quo, and transform a woman from reformer to prophet. In her estimation, Protestantism was the sole force responsible for the uplift of women, and women could use this particular form of Christianity to better themselves and the nation. White Christian motherhood could save the Klan’s white Protestant America. With the power to vote, Gill urged Klanswomen to take back their nation employing both maternalism and faith. For Gill, white women would make the difference in national politics; the right to vote was only the beginning. Motherhood allowed women to bring their authoritative voices to the political arena. Christian mothers knew best.

Robbie Gill was a maternalist, Christian, and white supremacist. While she encouraged women to participate in national politics, she also headed up the women’s auxiliary to the Klan, an order known for white robes, prejudice, racism, and burning crosses. Yet, Gill’s white supremacy and Klan leadership are not what interests me today. Instead, Gill’s language of white Christian motherhood as political authority appears again today in the rhetoric of contemporary conservative women. As I followed Michele Bachmann’s campaign for the Republican presidential nomination in 2012, I was reminded of Gill. Both used white Christian motherhood to claim political authority and power. To place Gill and Bachmann side-by-side showcases how Christian motherhood surpasses the bounds of mere support to become a legitimate claim for political power, including the office of President.

Mama Bachmann

Photogenic, energetic, and tough, Congresswoman Bachmann elicits much attention, though not entirely positive. Her evangelical roots, large family and foster children, the Tea Party caucus and chairship, her husband’s Christian counseling practice, and her own historical gaffes constitute the media spectacle of “Mama Bachmann.” Maternity and faith explain her political motivations, and analysis abounds about what Bachmann might mean for the Republican Party and the evangelical vote. Her Christian motherhood becomes a measure of authenticity, dedication, or even scorn.

The New York Times declares, “The roots of Bachmann’s ambition began at home.” The “stay-at-home mother and onetime federal tax lawyer” had a higher “calling” to open her home and her family (husband and five kids) to foster children. The Times further reports both motherhood and “evangelical Christian beliefs” led Bachmann to seek public office. The Washington Post profiled Bachmann’s husband, Marcus, and emphasized that they share “strong conservative values.” The article also emphasizes her wifely submission to her husband’s authority as “an article of faith within the family,” alluding to a concern that if elected President her husband would still demand submission.

Rolling Stone depicted Bachmann as a crusader in cross-emblazoned armor, dual wielding sword and Bible, as accompaniment for Matt Taibbi describes Bachmann as “a religious zealot whose brain is a raging electrical storm of divine visions and paranoid delusions.” CNN reported that the congresswoman from Minnesota “says God encouraged her to run for higher office.” D. Michael Lindsay, writing for the Washington Post, labeled Bachmann an “evangelical feminist.” Her emphasis on motherhood “humanizes her and differentiates her from the rest of the Republican field,” which is “political genius.” (For more on evangelical feminism, see Marie Griffith’s the genealogy of the term at the Huffington Post.)

Motherhood and faith define her, and sometimes the coverage assumes that her combination of the two is somehow distinct. What is distinctive is that her Presidential run emphasizes both.

As was clear from the media attention paid to Sarah Palin, the Mama Grizzly herself, Bachmann’s identity as a politician born of Christian motherhood has precedent. Last year, Lisa Miller described Palin’s emphasis on being a mother alongside her religious language in Going Rogue. Miller further argued that Palin’s popularity signaled that the Christian Right is now a women’s movement. Yet the presence of “Saint Sarah,” as Sarah Posner noted, did not signal that women are now leading the Christian Right. Rather Palin’s popularity with white evangelical women was in her similarity to them, their mutual resemblance as parents, wives and women. Palin seemed recognizable and familiar, and Bachmann does as well. While folks mull over Bachmann’s extremism, her Tea Party credentials, and her marriage, she presents a warm maternal authority steeped in evangelical language. Bachmann reaches out a hand for the nation to grasp, whether you want her to or not. For some, she is less off-putting and more approachable than Palin. If Palin chooses to run, the Christian mothers might have to fight it out publicly. And neither will go down without a fight. Christian motherhood might be political genius, after all.

What Kind of (Christian) Mother Are You?

What disappears in the discussion of motherhood and faith is the relationship of both to race. Palin and Bachmann are not just Christian mothers, but white Christian mothers. The emphasis on mothers as political leaders seems to skirt the pressing issue of race: which (Christian or not) mothers can (or cannot) have political authority? White mothers can.

And white mothers do as Bachmann’s recent signing of “The Marriage Vow,” a pledge sponsored by a conservative Christian organization named The FAMiLY LEADER. The pledge contains not only guarantees to protect women from the likes of porn but also claims that “black children born into slavery had better family structures than black children now.” Anthea Butler writes that this pledge is a “racially-coded” strategic move on the behalf of Republican candidates, including Bachmann, to “alarm” white conservatives. For me, the pledge signals that some mothers cannot protect (or legislate) their children as well as white Christian mothers. Maternal authority relies on both religion and race. The pledge lacks historical awareness to the institution of slavery as well as documents the so-called need for protect women. Bachmann’s signature attests to her authority as mother to know what is best for her family as well as the families of others, while also affirming the vulnerability of women.

The signing of the pledge is the moment in which the Bachmann and WKKK analogy becomes tempting. For Imperial Commander Gill, white Christian mothers had great power and influence, but her vision of Christian motherhood directly reflected the white supremacy of the Klan. Gill’s vision of maternalism was explicitly racist. So, what about Bachmann? She did sign a racist pledge and stands by her signature. What is her affinity to white supremacy?

For the WKKK, white mothers knew best. I hope that’s not the case for Bachmann as well, but I’m doubtful. Bachmann’s continual use of Christian motherhood as her identity, both personal and political, resonates with the WKKK’s earlier example. Unlike Gill, Bachmann’s maternal strategies move her from support to the possible Republican nominee. Yet I wonder if the strictures of Christian motherhood will limit Bachmann as they did Gill. Will this emphasis on Christian motherhood as a claim to authority backfire? Christian Right leaders rallying behind Texas governor Rick Perry might demonstrate that Christian motherhood is a not a fail-safe claim for legitimacy and political prowess, but it also means that Bachmann cannot be counted out yet.

***

Originally, I wrote this essay in March of 2012 for an online religion magazine, but it was never published. One of the editors was afraid that the comparison between the WKKK and Michelle Bachmann was “too dicey.” Just associating Bachmann with the Klan seemed like dangerous territory. The editor had me add a disclaimer about how I wasn’t calling Bachmann a racist or white supremacist, but rather I was just “comparing” their use of Christian motherhood as a political strategy. Even with the disclaimer, the magazine passed on the article. Now, five years later, we are in a moment in which we can’t dodge the discussions of white supremacy and politics (politicians), so I thought I would publish this essay here at my site. It’s lightly revised with disclaimers and previous hedging about white supremacy removed.

Pingback: White Supremacists and Racism - Cold Takes