Alright, folks, this is my attempt at a semi-regular weekly post to let you know what I reading this week, and perhaps, to encourage some of you to read along with me.

I’ll provide a short lists of the articles and books that I am reading/analyzing from week to week to showcase what projects I’m working on as well as to point some good scholarship too.

This week’s list includes:

1. Finding Presence in Mormon History:An Interview with Susanna Morrill, Richard Lyman Bushman, and Robert Orsi, Dialogue, 44:2, Summer 2011. (Thanks to Christopher Jones of both Juvenile Instructor and Religion in American History for this link.)

Here’s a snippet:

Robert: Again here’s an example where the language fails us. What is happening at these meetings in 1836 where there is an abundance of visions that are shared by lots of people, and people are speaking in tongues and seeing the heavens open? Modern historiography just stops at this point; it cannot deal with such experiences historically or phenomenologically. And as you say early on in the book, it appears that the only two options in modern historiography are either debunking such moments, claiming that the person at the center of it all is a charlatan and everyone else are dupes, or else translating the events into the language of the social: that it’s a matter of poverty, of people being on the margins of society, etcetera. But that leaves the central experiences unexamined and thus absent from history.

Richard: I agree with you entirely. You don’t have to dismiss all those other things; but if you were to talk about them to the people themselves, they might nod but would think we missed the point. One trouble is we get caught up in our readers’ struggles. If we had absolutely neutral readers, we might be able to do it. You suggest at the end that, to write understanding history, the historians must have a certain sensibility, but so do readers. They have to be willing to go with the flow, and that’s sometimes hard for them to do.

2. Robert Orsi, “2+2=Five, or the Quest for Abundant Empiricism,” Spiritus, 6:1 (Spring 2006), 113-121. (This is available via Project Muse with subscription). Here’s my favorite line:

The phrase “I am spiritual but not religious” unwittingly encodes this memory”: it means “my religion is interior, self-determined and determining, free of authority,” the opposite of that other thing, which in the history of the modern West means first “I am not like Catholics,” later “I do not belong to any church” (117).

3. Russell McCutcheon, “It’s a Lie. There’s No Truth in It! It’s a Sin”: On the Limits of the Humanistic Study of Religion and the Costs of Saving Others from Themselves,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 74:3 (September 2006), 720-750. (This is also available via subscription to Project Muse.) This article provides much to ponder, but I find appeal in McCutcheon’s terms “no cost Other” and the “too Other” (733) in describing the how and the why of religious studies. He uses the work of Orsi and Paul Courtright to discuss the costs of humanistic presumptions in methodology and urges readers to understand what it might mean that we employ different methods for the “no cost” and the “too Other.”

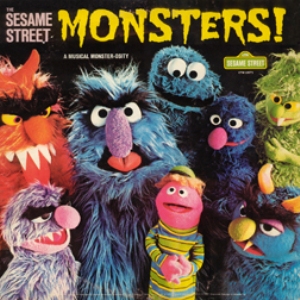

4. Stephen T. Asma, On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (OUP: 2009). Here’s the description from Oxford:

Monsters. Real or imagined, literal or metaphorical, they have exerted a dread fascination on the human mind for many centuries. They attract and repel us, intrigue and terrify us, and in the process reveal something deeply important about the darker recesses of our collective psyche.

Stephen Asma’s On Monsters is a wide-ranging cultural and conceptual history of monsters–how they have evolved over time, what functions they have served for us, and what shapes they are likely to take in the future. Asma begins with a letter from Alexander the Great in 326 B.C. detailing an encounter in India with an “enormous beast–larger than an elephantthree ominous horns on its forehead.” From there the monsters come fast and furious–Behemoth and Leviathan, Gog and Magog, the leopard-bear-lion beast of Revelation, Satan and his demons, Grendel and Frankenstein, circus freaks and headless children, right up to the serial killers and terrorists of today and the post-human cyborgs of tomorrow. Monsters embody our deepest anxieties and vulnerabilities, Asma argues, but they also symbolize the mysterious and incoherent territory just beyond the safe enclosures of rational thought.

5. Material Religion’s July 2011 issue on key terms in Material Religion keeps sucking me back in, especially the articles on belief (Robert Orsi), Medium (Birgit Meyer), Thing (David Morgan), and Words (Brent Plate).

6. What I want to be reading is Adam Mansbach’s recently released Go the F**k to Sleep, a mash-up of adult humor and a child’s bedtime story. Perhaps, I’ll just listen to Samuel L. Jackson read it to me instead.

Of course, this is only a taste of my weekly reading, but I highly recommend all of these resources. From methods to monsters appears to be my weekly goal, and of course, the Klan is always lurking in my mind, too, especially as I get promotional materials ready for the forthcoming book.

Happy reading!

P.S. For those of you always made nervous by the Cookie Monster, this very monster contemplate his monsterhood (years ago) at McSweeney’s. He asks the essential question, “Is Me Really a Monster?”:

How can they be so callous? Me know there something wrong with me, but who in Sesame Street doesn’t suffer from mental disease or psychological disorder? They don’t call the vampire with math fetish monster, and me pretty sure he undead and drinks blood. No one calls Grover monster, despite frequent delusional episodes and obsessive-compulsive tendencies. And the obnoxious red Grover—oh, what his name?—Elmo! Yes, Elmo live all day in imaginary world and no one call him monster. No, they think he cute. And Big Bird! Don’t get me started on Big Bird! He unnaturally gigantic talking canary! How is that not monster? Snuffleupagus not supposed to exist—woolly mammoths extinct. His very existence monstrous. Me least like monster. Me maybe have unhealthy obsession, but me no monster.

Pingback: On (More) Monsters: Figurative and Real : Kelly J Baker

Monster is an awesome REM album.