Music Saves

Sean McCloud

For some people, Jesus saves. For me, music saves. It always has and still does.

Coming from a shitty little poor town in rural northern Indiana, I was trapped by geography, class, and the limited mass and social media technologies of the 1970s and 1980s.

I grew up wanting to escape, but feeling confined by my surroundings and unsure of how I could ever get out (I mean, come on, a family “vacation” for my grandparents and me was a forty mile drive down state road 421/43 to the city of Lafayette to get groceries at Pay-Less and have dinner in the McDonald’s parking lot).

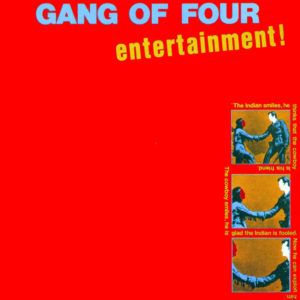

In my early to mid-teens—and especially after my grandma died a few days before my fourteenth birthday—music solidified as something that I could bury myself in, get my frustrations out through, and learn from. It was something affective that made me feel things with my body and brain. The music and lyrics to my favorite songs, albums, and bands put words to things that I vaguely felt but had no language for. Music helped me imagine a life outside of my hometown. Music taught me to question assumptions. And Gang of Four’s Entertainment!—perhaps more than any other album—initially pushed me to question things in such ways that continue to influence who I am and how I think today.

I remember it like it was yesterday. I bought Gang of Four’s Entertainment! in September of 1980 for $6.99 at Slatewood Records, a music and alternative press headshop near Purdue University in West Lafayette. Until it closed at the end of that year, it was a place of pilgrimage. I had three friends, and one of their fathers would occasionally travel to West Lafayette and drop us near the record and book stores. We would use our lawn mowing, hay bailing, and corn detassling money to buy records. Slatewood smelled so good to me. Incense was always burning, and even the brown paper bags you took your albums home in retained the store’s magical sacred scent long after it left the shop.

The year 1980 was significant for me in many ways, and one of them was in terms of music. Those Slatewood pilgrimages saw my friends and I start buying and sharing albums with each other that we didn’t hear on the few radio stations we could tune in to. In addition to the Gang of Four album, that year I also picked up Public Image Ltd.’s Second Edition, The Dead Kennedy’s Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, X’s Los Angeles, David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), and The Cure’s Boys Don’t Cry to add to my small record collection that by then consisted of records by The Sex Pistols, The Clash, Blondie, The Who, Pink Floyd, The Beatles, Black Sabbath, John Denver, Judas Priest, The Doors, and Ronco’s Fun Rock (my first album ever).

I was veering into a direction that would have me eventually immersed—as listener, concert goer, and musician—in punk, hardcore, and varieties of post-punk. But never just that. My tastes were always broad. I could and did love Bad Brains, Prince, the Heptones, and Stravinsky all at the same time. And how could I not find something such as producer Giorgio Moroder’s synth sequencers on the extended version of Donna Summer’s disco hit “I Feel Love” to be absolutely, mind-blowingly, fucking amazing? In a tiny town too small to have musical subcultures, my few friends and I nurtured parvenu eclecticism when it came to music, as well as most other things.

But as an early foray into post-punk, Gang of Four’s Entertainment! blew my fuzzed-out bar chord-loving mind. Musically it was tight—spastically and jaggedly so. From the opening seconds of the first song, “Ether,” to the final snare drum snaps of the album closing “Anthrax,” the guitar was used like a percussion instrument that sometimes resembled a buzz saw, the bass provided steady and almost robotically funky riffs, and the drums kept the guitar’s harmonics, feedback, and cuffed strums in tight time. The sound attempted to evoke anxiety, angularity, and angst. It was like nothing I had heard before and I loved it. But it was the vocals—which sometimes entailed two singers simultaneously taking on different roles and speaking two different sets of lyrics at once—that delivered phrases and one-liners that would remain embedded in my body and its thinking to this day.

Little did I know at age fourteen that I was being introduced, via music, to a hermeneutics of suspicion that I would later recognize (and embrace) in writers such as Pierre Bourdieu, Stuart Hall, and the Situationists. I could not have suspected–dancing around while someone repetitively sang “dirt behind the daydream”—that I would one day be an academic and writer whose formative view of the world was partly being inculcated at that moment via vinyl, needle, amplifier, and speakers.

As a fourteen year-old from a working-class background in rural Indiana, I wouldn’t have had the habitus or training to understand Bourdieu’s way of explaining that the world in which we live is filled with hierarchies, taxonomies, and valuations—promoted as natural, permanent, and fixed (to use Stuart Hall’s phrasing) —that work to advantage some groups at the expense of others. And, that this is the case even when the people advantaged are not fully conscious of the socially constituted and constructed nature of the categories that they benefit from. But the lines from Gang of Four ‘s “Natural’s Not In It” suggested to me just that, and did it with a tight-ass beat.

In other songs, containing other memorable chanted lines, the teenage me heard that history was not made by the so-called “great men” found in history books (“Not Great Men”); that news, advertising, and entertainments lull us into acceptance of our own oppression (“Ether,” “At Home He’s a Tourist,” “5:45,” “I Found That Essence Rare,” “Return the Gift”); and that our conceptions of love, relationships, and gender roles are less biological than ideological (“Damaged Goods,” “Anthrax,” “Contract”). Throughout Entertainment! one hears the tortured voice of the everyman/everywoman trying to negotiate some tiny amount of freedom in a world of constraint, residing in a place and time in which her/his life has largely been predetermined, and failing in nearly every moment—intimate and public—to live up to the roles and categories which they have been prescribed through no choice of their own.

Stuck in a small town that looked in some ways like the world of constraint, hierarchy, and unquestioned assumptions that the characters singing and sang about existed within, Entertainment! was one of the albums that pushed me into different ways of seeing, interpreting, and engaging the world. It still does.

List of some the things Sean McCloud has made in his life: detassled corn, short order food, semi trailers, music, and most recently books as a professor of religious studies at The University of North Carolina at Charlotte.