The Alchemy of R.E.M

Chris Hutchison-Jones

R.E.M. is my favorite band. I’ve had fits, flings, and flirtations with other artists; some are even recurring long-term affairs. But I always come back to R.E.M. Depending on the day, the weather, my mood, and the phases of the moon, my favorite album by my favorite band shifts. But if I had to pick one to be with me on that mythical desert island, it would be New Adventures in Hi-Fi. I’ll sit up straight in my chair and loudly proclaim it as my favorite album by my favorite band.

That R.E.M. is my favorite band is no great statement. They’ve sold millions of albums and influenced any number of bands and artists that have become integral parts of my own musical life. But NAHF somehow tipped the scales for me. It had virtually no hits. It was a mishmash of live recordings and studio tracks. The first single (“E-bow the Letter”) was a broody, half-spoken folk rock dirge with eerie backing vocals by someone I’d never heard of at the time, Patti Smith. Not the typical makings of a favorite album.

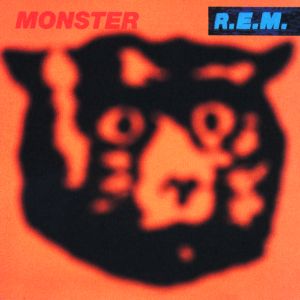

So, how did it happen? How does a band and album become a favorite? For me, the spark was “What’s the Frequency Kenneth?” off their previous album Monster (1994). R.E.M. was a part of my mid-1990’s alternative rock scenery, but this was different. The opening D chord was a fuzz-fueled shot across my bow. It was visceral experience, the sound and the visuals not what I associated with the band. Between singer Michael Stipe shimming like a late twentieth century Fred Astaire and guitarist careening onto the screen for a solo, I was gobsmacked.

Even physically, the album didn’t look like R.E.M. with its orange and blue motif and…bear head? No lyrics in the booklet, at least not full lyrics, but two panels of short phrases such as “look at me/immortal sad” and “yes I am fucking with you.” It immediately went into heavy rotation. In the 14 months between the album’s release and the corresponding tour coming within driving distance, I convinced my parents to let me go to the show in Orlando, Florida on November 15, 1995. This was a teenage eternity to wait, but at least it gave me time to memorize all of the sounds Stipe was singing because I sure as shit couldn’t make out all the words.

Even physically, the album didn’t look like R.E.M. with its orange and blue motif and…bear head? No lyrics in the booklet, at least not full lyrics, but two panels of short phrases such as “look at me/immortal sad” and “yes I am fucking with you.” It immediately went into heavy rotation. In the 14 months between the album’s release and the corresponding tour coming within driving distance, I convinced my parents to let me go to the show in Orlando, Florida on November 15, 1995. This was a teenage eternity to wait, but at least it gave me time to memorize all of the sounds Stipe was singing because I sure as shit couldn’t make out all the words.

Two things happened in the final lead up to the show. First, my friend Brian was supposed to come also, but his parents changed their minds. It was a school night, but 15-year-old-conspiracy-theory-Chris thought that Brian’s dad might have been jealous because he was an R.E.M. fan too. Second, in the last few days before the show a tropical storm hit close enough to Tallahassee, Florida to rip the roof off their civic center. The Tallahassee show was cancelled and not made up. I almost bought tickets to that show instead of Orlando. For me, the crisis was narrowly averted. The actual Orlando concert is now a bit of a blur. Yet, I distinctly remember the guy sitting in front of me turning around and asking me how I was able to sing along to the new songs. A friend had gotten me a bootleg from earlier in the tour that had several of the new songs. Damn, I felt cool.

NAHF was released in September 1996. Earlier that summer Brian and I had been floored by another new song that R.E.M. had played at the MTV Music Awards. We didn’t know the title, but it rocked, and I think Stipe sang something about “lunch meat” and “pond scum”? Brian and I left school on the release date in my 1995 Toyota Tercel and went straight to buy it. We talked nonstop about that new song and wondered if it would be on the album. Song number two sounded familiar, and then the lunch meat/pond scum confirmation. As I drove Brian home, we listened to that song (“The Wake-Up Bomb”) on repeat.

After the initial jolt of “The Wake-Up Bomb” the rest of the album began to sink in, some of which I already knew from the bootleg tape. There was no retro orange/blue distortion on the cover like Monster. In its place was a black and white still photo of a moving desert horizon. No cryptic half-poems in the liner notes, instead a breakdown of where every song was recorded. One of them, “So Fast, So Numb”, was even recorded at sound check of the Orlando show! The first single wasn’t a blast of radio-friendly unit shifting alt-rock, it was a minor chord dirge with a video to match. All blue-green banal, dim white Christmas lights, and Stipe staring out of bus windows. How the hell is he so compelling just looking out the window, using eye drops, and lip syncing only every other line? The song touched something in my chest rather than my pelvis. The album as a whole was written in the motion of the Monster tour (or its immediate aftermath) and that motion was reflected in everything from the cover, to the song titles (“Departure”, “Leave”, “So Fast So Numb”), and the lyrics. The whole package seemed to vibrate and hum of its own accord.

Now, how do I push this moment to its crisis? I signed on to write about how NAHF is my favorite album by my favorite band. Maybe even touch on how a band became my favorite band. I’ve set the table. I’ve ruminated, marinated, pontificated, and purged (painfully from earlier drafts). I had outlines, notes on lyrical interpretations, analysis of the recording process, clichéd coming of age stuff, a half-baked metaphor comparing the album to a snow globe in reverse (sounding awesome in my head but making less literal sense then some of Stipe’s lyrics), but none of it could singularly get me to the goal. Like the band, and the album, I’ve settled on the idea that my love for both is greater than the sum of its parts. An alchemy that does not correspond to the elements as they appear on the periodic table. But how do I write it without stripping it of all the marrow that made it living bone?

NAHF was released at the beginning of my senior year of high school. But this is not nostalgia rock for me. That’s too simple, too easy (or is it too close to the truth?). Listening now I am not immediately transported back in time. Those moments are at a comfortable distance that could be accessed if needed, but it’s not about them. In hindsight, I internalized the album into the soundtrack of starting to be my own person with something distantly resembling confidence. There was little to no cultural capital to be gained by me waxing poetic about the album then (or now), but I did and that emboldened other declarations about the intrinsic value of other less than helpful enhancers of social status (the Indigo Girls, Oasis, and the Counting Crows to name a few). It was the beginnings of trusting my own inner critic as a songwriter and guitarist. But NAHF is still with me in a way that those other albums and bands are not. The album was about movement, not a particular move, so it moves with me just as well at 37 as it did at 17.

There were lots of trinkets that held my 17-year-old sway that barely register on my barometer now. Back then, Kerouac the dharma bum screamed at me as only a bodhisattva could. Now he’s a high school friend I’d have a beer with only occasionally, and I certainly wouldn’t let him babysit my kid.

NAHF is still immediate and always welcome at the table.

In summer of 2014, my very pregnant wife encouraged me to go see a band called The Baseball Project at Great Scott in Allston, MA (a stage small enough that I’ve even played on it). While original songs about baseball were exciting, most importantly the band consisted of half of R.E.M. (Peter Buck and Mike Mills). As the show approached, I became increasingly excited to possibly meet two of the guys responsible for my infatuation with ringing open chords.

Monitoring their Facebook page it looked like Buck, an only occasional member of the band, wasn’t on this tour. I almost decided not to go, but the night of the show I loaded NAHF into the CD player and headed over to the club before the doors open (because I never was cool). And there he fucking was, walking right toward me in the empty club. I gathered my fleeting gumption and babbled something to Buck about wanting a “fan boy moment” that he graciously humored. I think I told him that he influenced my approach to songwriting (why do a solo when you could write a bridge?) while fumbling my phone to take the obligatory selfie. Later Buck tried to upsell me at the merch table to buy a vinyl box set of The Minus 5 for $100. I should have said something about how my pregnant wife wouldn’t have been too keen on the purchase, but I had no such snappy retort.

After the show, I made a less expensive purchase and headed for the door. Mike Mills was standing alone. Somehow I ended up talking with him about my childhood memories of watching Cubs games on TV and listening to the drunk Harry Carey sing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.” Mills snickered and said that every kid should have that memory. I took my leave, without available autographs or more photos. I decided I had all I needed so went back to the car and NAHF.

In a bit of historical revisionism, I swear I mentioned to either Buck or Mills that NAHF was my favorite album, and there was some sort of acknowledgment of my comment. A wink, a nod, something. There was something in the interaction that was mine. It was greater than the sum of its parts; it made perfect sense to me. Just like NAHF, still my favorite album by my favorite band, and I’m still not sure I can plot out exactly why.

And if I could, I’m not sure I’d want to.

Chris Hutchison-Jones is a Licensed Independent Clinical Social Worker who supports clients struggling with addiction and mental illness in the Boston area. Chris earned his MSW at Boston University and a MA in Religion, Philosophy, and Ethics at Florida State University. In his spare time he writes songs for a variety of acoustic instruments including, to some friends’ and family members’ chagrin, the banjo. He is also working to impart his love of old American folk and blues music to his son. He hails from northeast Florida and central North Carolina. His favorite R.E.M. song is “Country Feedback”, which is not on New Adventures in Hi-Fi.